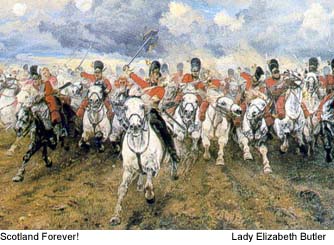

The Royal Scots Greys at Waterloo

Did it really happen this way?

Probably not…

” …The Greys moved straight to their front, through the ranks of the Gordons. The head of the French Division was now only 20 yards away and the Greys simply walked into the 1st/45th Infantry of the Line. There was no gallop and no charge.”

Comments on the Charge of the Royal Scots Greys at Waterloo by W. A. Thorburn, late curator at the National War Museum of Scotland

Composition of the Regiment in 1815

Up to the return of Napoleon from Elba, the Royal North British Dragoons (Scots Greys) had 8 troops, but in 1815 this was increased to 10 troops, the total strength of officers and men in the 10 troops being 946.

Only 6 troops went to the Netherlands to join Wellington — 4 remaining at Ipswich. The officers who went with the 6 troops were Lt. Col. James Inglis Hamilton and Majors Isaac Blake Clarke and Thomas Pate Hankin. The Adjutant was Lieutenant Henry McMillan; Assistant Surgeon James Alexander; and Veterinary Surgeon John Trigg. The captains were Edward Cheny, James Poole, Robert Vernor, Thomas Reignolds, Charles Barnard, Thomas Fenton and Edward Payne. These captains commanded the 6 troops except Reignolds who was a Brevet Major and was Brigade Major to Sir William Ponsonby. The Lieutenants were John Mills, Francis Stupart, George Falconer, James Wemyss, James Carruthers, Archibald Hamilton,Thomas Trotter, James Gape, Charles Wyndham and James Graham. These were 3 cornets: Edward Westly, E.C. Knichant and Lemuel Shuldham.

The troops varied in strength at various times, but the normal strength was about 70 to 80 men. However, at Waterloo the Union Brigade (formed by the Greys, Royal Dragoons and Inniskilling Dragoons) with a paper strength of 1150, only mustered 900 sabers altogether, the Royal Dragoons and Inniskillings, like the Greys, being represented by 6 troops each.

The French Advance

When the battle started, the Union Brigade was posted to the rear of Picton’s infantry division; the Greys at the left rear of the Inniskillings, who were in line with the Royals on their right. Pack’s Brigade of Picton’s division, consisting of the 55th , 92nd (Gordons), 42nd (Black Watch) and 1st Foot (Royal Scots), were in front of the Inniskilling Dragoons and Greys. The Royal Dragoons were further to the right, behind Kempt’s Brigade (28th Foot, 79th (Camerons) and 32nd Foot).

The French advance was made by d’Erlon’s Corps, which consisted of four divisions; those of Marcognet, Donzelot and Bourgois being front of Picton’s division with Marcognet heading for Pack’s brigade. French divisions were composed of 4 regiments, each regiment having 2 battalions; 2 regiments or 4 battalions forming a brigade.

The French attack was made in divisional columns, the leading battalion of the leading Brigade being only about 15 files wide. Marcognet’s Division was led by the 1st battalion, 45th Infantry of the Line commanded by Colonel Chapuset. Intervals of 5 or 6 yards separated the battalion columns. The column method has been much criticized; although it presented a very small front, and a theoretically well protected continuous flank with high fire potential, the whole mass of troops was difficult to control if the “wedge” method of attack was disrupted. As each battalion closely followed the one in front of it, as a continuous formation, deployment from the front could cause confusion.

The 1st/45th at the head of Marcognet’s Division appeared in front of the 92nd (Gordons) and at a distance of only about 30 yards, began to deploy. At this point they received a volley from the Gordons who were very hard pressed and likely to be overrun. Donzelot’s Division, although not so close, menaced Kemp’s Brigade.

The Counterattack by the Union Brigade

The Union Cavalry Brigade was now ordered forward. The Inniskilling Dragoons passed through the ranks of the Royal Scots and the Black Watch, and the Royal Dragoons, further to the right, went through the 28th Foot and passed the right flank of the Royal Scots.

The Greys, who had been in a theoretical reserve position, moved straight to their front, which took them through the ranks of the Gordons. The head of the French Division was now only 20 yards away and the Greys simply walked into the 1st/45th Infantry of the Line. There was no gallop and no “charge.”

It is clear from the French report that they did not expect to see British cavalry materializing through the ranks of the British infantry. When the cavalry hit them, the 45th were in the act of forming line, and their 1st battalion was at once thrown into violent confusion, already shaken by the fire of the 92nd. The regimental eagles were carried by the 1st battalion of all French infantry regiments, and in a few minutes the Greys were in the midst of the battalion, at which stage Sergeant Charles Ewart of Captain Vernor’s troop captured the eagle of the 45th. He was ordered to take it to the rear, which he reluctantly did, but sat on his horse for sometime watching the engagement before finally setting off for Brussels with his trophy.

The rest of the French columns believed what they saw could only be an advance guard, and were now under the mistaken impression that they were being attacked by large numbers of cavalry. The Royal Dragoons and Inniskilling charged Donzelot’s Division and the Eagle of the 105th Regiment was taken by the Royal Dragoons. These were the only two Eagles captured during the entire Waterloo campaign.

At this point the divisions of Marcognet and Donzelot were not completely shaken, although contrary to romantic legend, the Union Brigade did not, and could not, defeat at Army Corps of some 16,900 infantry on their own. Having carried out a highly successful defensive action in support of infantry, the Union Brigade lost all cohesion and refused to recognize or hear any orders. The Greys were given the “recall” several times but were so out of hand that no notice was taken. Instead they went off on a wild rampage down the interval between the French Divisions, NOT through the troops themselves; many Greys when shot by the surprised and somewhat bewildered rear French battalions, who were still advancing, unaware of the confusion on their own front, or of the defeat of their leading brigade. In fact, the French infantry, expecting what they thought must be the main cavalry attack (by their own massive standards), finally brought themselves to halt, made an effort to form “to receive Cavalry”, and finally fell back in considerable confusion.

The Union Brigade is Destroyed

Meanwhile, the Greys were no longer a regiment of cavalry but a disjointed series of ad hoc detachments, just galloping about cutting at whatever they could see. A few got to d’Erlon’s divisional artillery batteries, by which time the inevitable French reaction was under way. Lancers attached to d’Erlon’s Corps were set in motion, as was Milhaud’s Cuirassier Division. Travers’ brigade of Cuirassiers (7th and 12th Regiments) collided with the British Household Brigade which was composed of the Life Guards, Royal Horse Guards, and King’s Dragoon Guards. Farine’s Cuirassier brigade (6th and 9th Regiments), also from Milhaud’s command, went for the scattered Union Brigade.

This highly dangerous French cavalry force created havoc among the British regiments. After their brush with the Household Brigade, the 7th and 12th Cuirassiers also became involved in chasing down the scattered remnants of the Union Brigade. In fact, the 7th Cuirassiers claim the credit for the destruction of the “Grey Scots Dragoons”, although it was the 6th and 9th who arrived on the scene first. The Greys’ casualties were very heavy and they could only attempt to find their way back in small groups. While they strove to shake off the well controlled charges of the cuirassiers, the 3rd and 4th French Lancers got between them and the British lines, not that the confused Greys Troopers by now were quite sure where they were!

One of the myths of Waterloo is that the 45th of the Line was an elite formation. No French regiment was called the “Invincibles”; this was invented by British enthusiasts to enhance the value of their captured emblem. The 45th was a line regiment recruited in Paris, and their only nickname was “Les Enfants de Paris.” The 45th was simply unlucky enough to be at the front of the force struck by the Greys. Their eagle was the standard issue to all French regiments; in fact, it and the regimental color are “Hundred Days” pattern, i.e., a utility version of the more elaborate 1812 model, turned out in a hurry during the months before Waterloo to replace those destroyed by order when Napoleon was sent to Elba. The eagle and color are now preserved in the National War Museum of Scotland (formerly the Scottish United Services Museum). The Napoleonic eagle did not become a Greys badge until 40 years after Waterloo. Even this is given extra significance, as it has the laurel wreath awarded only to an elite group of French regiments, of which the 45th was not one.

Sergeant Ewart

Charles Ewart was born in 1769 at Bedoes farm near the source of the Clyde near Elvanfoot and worked on the farm until he went to Kilmarnock — the nearest recruiting center — and enlisted in the 2nd Royal North British Dragoons in 1789 at the age of twenty. He took part in the campaigns in the Low Countries of 1793-1795 and was taken prisoner for a short period. During the retreat of the British Army through Holland, he was noted for his discipline and strong character, and was soon promoted to sergeant. By the time of Waterloo he was 45 years old and a veteran of 25 years with the colors. He was fencing master of the regiment, and respected by all ranks. He was reasonably educated for the period, and could read and write and found no difficulty in conversing with his officers.

After the capture of the Eagle at Waterloo, he was paraded around the country bySir Walter Scott, and made to give speeches at dinners and receptions about his feat at the battle. He was himself a simple and honest soldier, but certainly the story got larger by the telling, to people eager to establish the feeling of great victory on the basis of this one episode, so that in time the destruction of his regiment became forgotten — only the few minutes of glory remained. Ewart himself regretted having to leave the field with the trophy, waiting for sometime before ordered again to take the Eagle away from the battle.

He was given the Freedom of the city of Irvine and lionized in Kilmarnock where he had enlisted. The regiment gave him a silver cup some years after Waterloo; sadly, this was stolen from him and never seen again. As a reward for his services, Ewart was given a commission as an Ensign (2nd Lieut.) in the 5th Veteran Battalion in February 1816. This unit of old soldiers was disbanded in 1821, and he retired with the full pay of an Ensign for life. He was married but had no children so there is no direct male line. He spent his last years at Davyhulme near Manchester. He died there in March 1846 aged 77, being buried in the graveyard at Salford. Over the years the grave became covered and forgotten. In the 1930’s it was found under a builder’s yard, and in 1938 the regiment reburied his remains on the esplanade of Edinburgh Castle.

This article is reprinted by permission from the Scabbard, Journal of the Military Miniature Society of Illinois.

© 1998 Military Miniature Society of Illinois.