SOULS NOT WANTING: THE MARSHALATE’S BETRAYAL OF NAPOLEON

By Claudio Innocenti

“Sire, the army will obey its leaders.” With these words, Marshal Michel Ney, at the head of a cabal of French marshals, mutinied against Emperor Napoleon I on the morning of April 3, 1814, at Fontainebleau. Napoleon wanted to attack the Allied occupying army in Paris, but his marshals refused to carry on with the campaign. Two days later, Marshal Auguste Marmont ordered his corps straight into the center of the Allied army, where it surrendered. Thus, Napoleon was betrayed by men who he had fought with for over fifteen years, and without the support of these men he was forced to abdicate his throne. Napoleon, with the marshals leading his corps, had won countless victories while campaigning in Italy, Egypt, Spain, Germany, Austria, Poland, the Balkans, and Russia. Ironically, Napoleon’s most desperate campaign, fought in 1814 to save both his throne and his country, was ended by the very men he most counted on to defend France: his marshals.

In 1814, France faced the prospect of an enemy invasion for the first time in nearly twenty years. Napoleon suffered 500,000 casualties in Russia in 1812 and again in Germany in 1813, and in 1814 he faced a coalition of four major powers and numerous smaller nations that would invade France from the south, the southeast, and the east. Napoleon’s maneuvers with his small army were some of his finest, but the Allies steadily advanced through France anyways and captured Paris in three months. Even then, Napoleon felt he could convince the citizens of Paris to attack the Allies inside the city, while he cut off the Allied lines of communication with his field army. It was at this moment that his senior marshals turned on him. Once the Allies saw that even Napoleon’s oldest comrades would no longer fight by his side, they demanded that Napoleon abdicate. Most historians argue that Napoleon’s marshals betrayed him because they were weary of nearly twenty years of constant war, because they did not want to see Paris destroyed, and because they felt they could spare France from further destruction by forcing Napoleon to give up his throne. These reasons certainly contributed to the betrayal; however, it was Napoleon’s miscommunications during the 1814 campaign which led to severe defeats of the marshals’ individual corps, and which ultimately severed the link between them and Napoleon.

The Campaign in France, 1814 by Meissonier

Paris was the administrative, cultural, and commercial center of France in 1814, and the marshals did not want to fight in the city. However, some memoirs of French officers claim that their troops were certainly willing to attack an Allied-occupied Paris. Still, many of the marshals, high-ranking generals who were also part of the Napoleonic aristocracy, had family or property in Paris, and so they were wary of attacking the French capital for personal reasons. Because an attack on Paris would require its citizens to tie down Allied troops in hand-to-hand fighting, the potential damage to the city was significant. In fact, the men ultimately charged with defending the capital, Marshal Marmont and Marshal Edouard Mortier, fought for less than a day in front of Paris. As soon as the Allies approached the city itself, the marshals quickly signed an armistice that ensured the city would suffer no further damage. Frederick Maycock believed that this refusal to fight inside of Paris was evidence of a general fear among the marshalate that Paris would be damaged. Once Paris was occupied, the rest of the marshals believed the war was over, and they opposed a full-scale attack by Napoleon’s army and the Parisian mob that would destroy more of their beloved capital. Throughout the marshals’ memoirs, they often claimed that they did not want to attack Paris and see it destroyed as Moscow was in 1812. The marshals were simply not willing to sacrifice the political and cultural heart of France to the uncertainty of battle. Nevertheless, they were experienced, professional soldiers raised from the ranks of the French army, and they would probably have supported an attack on Paris if they felt it could end the Allied invasion. Unfortunately, by April 1814 the marshals had lost faith in Napoleon’s ability to secure a victory, because his inability to communicate his strategy led to disastrous defeats for the French army during the campaign. While the marshals were not eager to attack Paris, they were even less eager to continue following Napoleon, whose repeated miscommunications were the primary reason the Allies captured Paris.

The marshals would later argue that they mutinied at Fontainebleau to save the rest of France from Napoleon’s refusal to negotiate a peace. The marshals believed that by keeping the main army intact, they could negotiate from a position of strength, and force the Allies to compromise with Napoleon. Once the Allies were in Paris, the marshals believed an attack on the city would fail, so they mutinied to spare France from Napoleon’s stubborn willingness to continue fighting. The marshals’ mutiny convinced Napoleon to abdicate in favor of his son, eliminating the real obstacle to peace: Napoleon himself. David Markham argues that the marshals, by abandoning Napoleon while he still had an unbeaten army in the field, believed they could ensure the Bonaparte dynasty continued to rule France. Even some Russian historians like Alan Palmer argue that the marshals mutinied in order to show Napoleon that peace must be sought out at all costs. If the army was destroyed in an attack on Paris, the Allies would be able to impose any sort of peace they wanted on a defenseless France. On the other hand, if Napoleon destroyed the Allied army in Paris, then he might return to conquering the rest of Europe and restoring his military supremacy on the continent. The marshals could only ensure a Bonapartist succession if the army appeared willing to die to the very end for Napoleon’s sake. But the mutiny at Fontainebleau and the defection of Marmont’s corps made the army, still strong and capable of fighting, appear weak and disunited. Although Napoleon refused to negotiate after losing an entire army in Russia in 1812 and again in Germany in 1813, the marshals did not force him to make peace. Ironically, when Napoleon had a rapidly growing and intact army south of Paris in April 1814, the marshals finally did force peace on him. It was not just that they were tired of his refusal to negotiate; they were tired of how his inability to communicate had cost them the 1814 campaign, and so they betrayed him to end the war.

These schools of thought address in some way why the marshals felt disenfranchised and ultimately turned on Napoleon. They were certainly weary of war, but these were tough men who had fought in dozens of engagements in every major country on the continent, and they all stubbornly fought throughout the entire 1814 campaign despite their length of service. Only when Paris fell did the marshals truly feel they needed to try and force peace on Napoleon. They were wary of damaging Paris, but they would probably have agreed to attack the city if they had confidence in the plan of attack and in their commander. They were tired of Napoleon’s refusal to negotiate with the Allies even after Paris was occupied. Although they were shocked that Napoleon had no intention of making peace, he had suffered severe defeats in previous campaigns and had not made peace with the Allies then. The main reason they no longer believed in Napoleon was because of his failure to communicate his strategic vision and operational plans to them. Throughout the campaign, marshals commanding small corps were left to their own devices, while Napoleon was off elsewhere trying to achieve a decisive battle. While the entire point of the corps system was to use individual corps to tie up enemy forces while one concentrated at a certain point, this is not how the 1814 campaign played out. Instead, the marshals often found themselves with a few divisions and no clear directions, whilst facing much larger Allied formations. If the marshals withdrew, they gave up key territory that could not be easily recovered and would be chastised by Napoleon for it; if they stayed and fought, they would see their smaller units consumed up by the Allied juggernaut.

By failing to clearly communicate either his strategy or his plans, Napoleon left the marshals only two choices when facing an Allied army: withdraw and abandon key territory, or fight and suffer horrendous casualties. The Allied invasion began in January 1814 and made significant headway while Napoleon remained in Paris to reorganize his armies. But in late January Napoleon took command of his field forces, and began a series of maneuvers that almost destroyed the Allied coalition in February. Key miscommunications prevented decisive victories against the Allies, and made the marshals feel that the campaign was simply dragging on for no reason. In March, the Allies regrouped and drove on Paris, and Napoleon’s inability to communicate led to outright defeats. After these losses, Napoleon marched away from Paris and left some of his marshals on their own to defend the capital, causing them to suffer additional defeats and lose Paris. Finally, after Paris fell at the end of March, Napoleon sought to bring the Allies to battle in his capital. He failed to convince his marshals of the need to attack, and also of the probability that it would succeed. By then, the marshals were fed up with Napoleon’s failure to communicate, and they betrayed him in order to stop the war.

LOST VICTORIES, FEBRUARY 1814

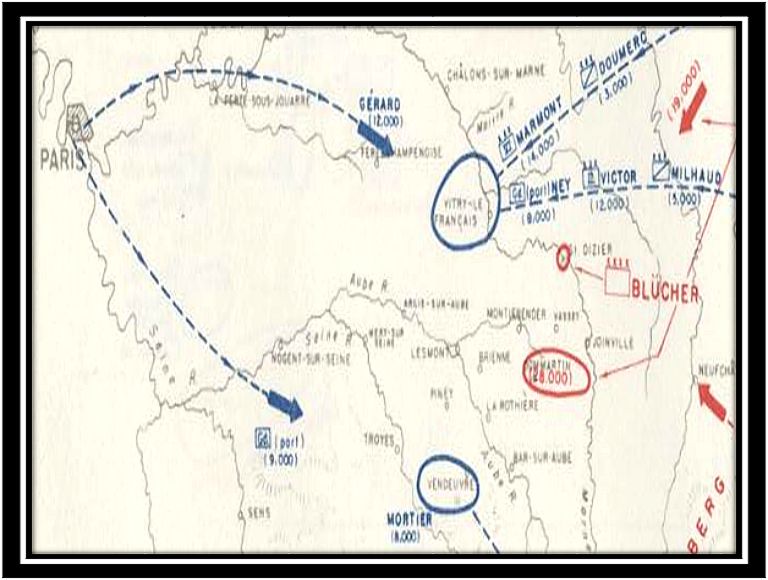

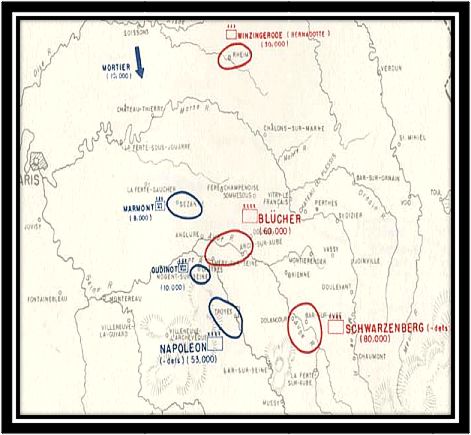

The Allies crossed the Rhine River and invaded French territory on January 1, 1814. They wanted to prevent Napoleon from rebuilding his army after his crushing defeat at Leipzig, and so the usually cautious Allies instead opted for a winter campaign. While Napoleon raised new formations from cadres drawn from Spain and Italy, he left his marshals with the remnants of his main army (about 100,000 men) to cover a 300-mile line stretching from the Netherlands to Switzerland. Marshal Jacques Macdonald held a typical command on the left bank of the Rhine: while assigned 60,000 men by Napoleon, he was given only 13,000, and had a mobile force of just 3,000 men to counter any Allied river crossings. The marshals retreated from their defensive line on the Rhine in the face of two Allied armies totaling over 300,000 men, and French units began withdrawing westwards into the heart of France. Eventually, Napoleon took direct command of his armies and was able to win a series of victories, even though his poor communication with his marshals prevented these victories from being decisive.

Position of Mortier’s Old Guard Relative to Prussian Army of Silesia, 26 January, 1814

Napoleon repeatedly failed to ensure his marshals knew his operational plans for conducting the 1814 campaign. When Napoleon left Paris with a small force of 35,000 men, he decided to attack the unsuspecting Prussian Army of Silesia at Brienne on January 29, 1814. Napoleon wanted to launch a frontal attack on the Prussians, while Marshal Edouard Mortier’s 10,000-man Old Guard attacked the Prussian rear. Mortier’s original orders from Napoleon, dated January 27, had him marching either southeast to Bar-sur-Aube or northeast to Vitry, depending on where the Old Guard was when the letter reached Mortier. While Napoleon was flexible with his orders and gave Mortier some latitude on which direction to go based on when the marshal received the order, this letter simply prevented a confused Mortier from marching to Brienne in time to attack the Prussian rear. When Napoleon finally did revise his orders and clearly specified that Mortier should come to Brienne, only one messenger was sent, and he was captured. Field Marshal Gebhardt von Blücher, the Prussian commander, extricated his men from the trap at Brienne, suffered only a minor defeat, and concentrated his forces away from Napoleon’s main body. Marshal Louis Berthier, Napoleon’s chief of staff, usually sent orders via three messengers on three different routes. That this did not happen at Brienne, the first battle Napoleon fought on French soil in 1814, showed a certain amount of sloppiness in the French victory. While one mistake does not mean the entire French system of communication was inefficient, on this occasion it prevented a decisive victory. The indecisive victory was the price Napoleon paid for keeping less capable subordinates under his immediate control. The men most adapt at independent command, like Marshals Louis Davout and Jean Soult, commanded their own forces in far off areas like Germany and Spain. However, in France Napoleon kept a tighter rein not only on his operations, but also the marshals leading corps under his direct command. Napoleon relied on these marshals to carry out his plans, but the marshals he picked for this campaign were those most in need of micromanagement and clear communication. Napoleon failed to specify his plan for attacking a larger coalition, and for destroying its individual armies in detail. If Mortier had known exactly how Napoleon wanted him to operate, he would have known to hit the Prussian rear, and thus the loss of a messenger and unclear orders would not have prevented Napoleon from crushing a surprised Prussian army.

Isolation of Macdonald’s Eleventh Corps, 1-7 February, 1814

Napoleon’s Concentrated Attacks on the Army of Silesia, 10 February, 1814

Since Napoleon preferred keeping a tight leash on his subordinates during this campaign, his marshals hesitated to move without express orders from the Emperor. Macdonald was an intelligent man with experience leading large, independent formations. In 1812, he commanded 32,500 men on the left flank of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, which operated apart from Napoleon’s main body throughout the entire invasion. In 1813, Macdonald even commanded his own army: the 80,000 man Army of the Bober, although it was routed at the Battle of the Katzbach. Macdonald was capable of at least corps-level command and independent action, but in February 1814, he had an unspecified number of Prussians in front of his men during the action at Montmirail. Considering he spent the previous week retreating in the face of this same force, he hesitated to advance against the Prussians without clear orders from Napoleon, which Macdonald never received. While in the midst of battle at Montmirail, Napoleon wrote to his brother Joseph on February 11 that he “supposed the Duke of Taranto [Macdonald]” would arrive in the rear of the Prussian army (located at Chateau-Thierry), and thus help secure a great victory with the destruction of two Allied corps. Instead, Macdonald, after seemingly being abandoned near St. Menehould and then forced to abandon Chalons without a fight, simply rejoined Napoleon’s main army, having somehow failed to discern his emperor’s plans for this part of the campaign. In his memoirs, Macdonald claimed that “these victories had no result save that of prolonging our agony,” demonstrating his later dissatisfaction with Napoleon’s inability to organize a decisive victory against the Allies. While by the time he wrote his memoirs Macdonald knew the outcome of the 1814 campaign, he still took the time to mention the futility of the half-victories of February. Still, as long as the French were victorious, miscommunications were merely a characteristic of Napoleon’s campaign style, and not an obstacle that would cost him the campaign and ultimately drive his marshals away.

Exposed Position of Marmont’s Sixth Corps’ After the Battle of Vauchamps,

and Napoleon’s Shift South Against the Army of Bohemia, 16 February, 1814

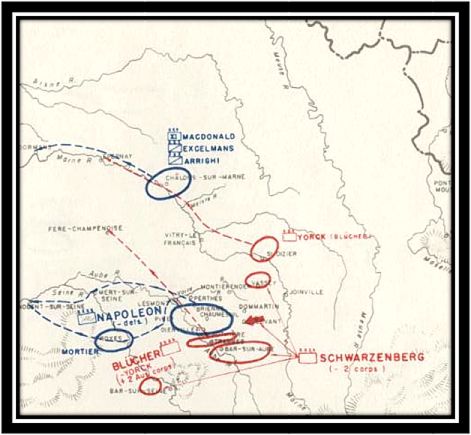

Exposed Position of Marmont’s Sixth Corps’ After the Battle of Vauchamps, and Napoleon’s Shift South Against the Army of Bohemia, 16 February, 1814 While previously Napoleon’s miscommunications left other corps too weak to fight on their own, as the campaign progressed Napoleon’s orders left corps under his direct command strung out and vulnerable to defeat. The Emperor ordered a pursuit after Montmirail, and defeated Yorck’s corps again at Chateau-Thierry. This time, the Prussians retreated over the Marne River, which put a halt to the French pursuit north. Napoleon sent Marmont’s Sixth Corps east to assist in the pursuit of other retreating elements of the Prussian army. The Bulletin of the Grande Armee of 15 February, printed in Paris, actually claimed that Blücher’s Army of Silesia was annihilated in three days. While Napoleon often embellished his army bulletins, he did not believe he exaggerated this one, especially since he left only a small, under strength corps chasing after an entire army he believed incapable of resistance. Inevitably, Marmont ran into a concentrated Prussian force nearly twice his size at Etoges, and soon retreated west to Vauchamps to rejoin the main French force. This Prussian advance, after driving back Marmont’s corps, was wedged between Napoleon’s army to the north and Marshal Claude Victor’s Second Corps at Sezanne to the south. Napoleon had dangerously overestimated the extent of his three previous victories, and believed the Prussian army to be broken and demoralized. Napoleon’s erroneous estimation of his own victories clearly convinced him to keep Marmont’s tiny corps chasing after an entire army that he believed no longer capable of resistance. Instead, Marmont barely managed to rescue his men from this tricky situation, and the Prussians chose to move north rather than to attack Victor’s vulnerable flank.

Eventually, Napoleon secured another victory over the Prussians, and he finally felt he could forget about them and concentrate entirely against the Austrians. Marmont had nearly met with disaster, and Victor had almost found his men facing the combined weight of the two Allied armies. Nevertheless, on February 14 the Prussians were finally routed at Vauchamps and lost nearly 7,000 men. Once again, despite his poor communication, the French Emperor was able to pull off a victory. Napoleon believed he had knocked the 80,000 man Army of Silesia out of the war, and once more he left Marmont and Mortier on their own while he moved south to face larger threats. While the marshals were certainly glad to be back on the winning side, these victories cost the much smaller French army a significant number of casualties, and Napoleon’s miscommunication prevented the total destruction of the Prussian army. In particular, Marmont’s men constantly marched back and forth due to Napoleon’s ever-changing and unclear orders, and eventually such orders had led them straight into the heart of the Prussian army. Marmont was saved from Napoleon’s mistakes by the emperor himself at Vauchamps, but serious fractures began to appear not only in Napoleon’s communications with his marshals, but in his relationships with these men.

Occupied with fighting the Prussians in the north, Napoleon gave far less concern to his subordinates facing a much larger Austro-Russian army. Marshals Nicolas Oudinot’s Seventh Corps (25,000 men) and Victor’s Second Corps (14,000 men) held the line of the Seine River in the face of Field Marshal Karl Schwarzenberg’s 150,000 man Army of Bohemia. On February 12, this Allied force finally crossed the Seine, and Victor and Oudinot simply could not hold the river line in the face of such overwhelming odds. Napoleon ordered Oudinot (with Victor providing support) to defend the bridges at Bray, Montereau, Pont-sur-Yonne, Moret, and Montargis. In the face of such an impossible order, Oudinot withdrew northwards, and this forced Victor to withdraw in this direction as well. Although by February 16, Napoleon had defeated the Army of Silesia and sent it reeling, the larger Army of Bohemia moved inexorably forward and threatened to both uncover Napoleon’s rear and advance on Paris. Napoleon had given Oudinot and Victor a task they could not accomplish, and had left them to fend for themselves on the Seine while he tried to bring the Prussians to a decisive battle. Convincing himself for the second time in two days that the Prussian army was destroyed and no longer a threat, Napoleon moved south with the bulk of his army. On February 16, Napoleon linked up with Oudinot and Victor near the Yerres River, and over the next two days he attacked southwards at Mormant and then Montereau. In the resulting battles the Allies lost 8,000 men and retreated back over the Seine. Napoleon ordered Victor to seize the bridge at Montereau to prevent the Austrians from retreating, but Victor’s corps fought from dawn until 7:00 p.m., at which time it finally did seize the bridge, albeit too late to do anything useful. Once again, Napoleon’s communication system appeared to break down at the critical juncture between a minor victory and a decisive battle. He ordered Victor’s men, leading the advance guard of his army, to cut through the enemy army and seize a bridge in its rear, while at the same time preventing the Allies from escaping over it. If Victor was sent on some sort of flanking maneuver, this may well have been possible, but there was no way his corps could push a much larger Allied army back over a bridge, then somehow seize that same bridge and prevent the Allies from crossing. Victor lost his corps command for his tardy arrival at the bridge at Montereau, even though he would later receive two Young Guard divisions by Napoleon anyways. Due to Napoleon’s poor communication with his corps commanders in 1814, Victor almost found his corps trapped between the two Allied armies two different times, and at the same time he had to maintain an impossible defense of the Seine. Victor was relieved after winning a fierce battle against much larger odds just because he could not accomplish a feat that was physically impossible. With one of their own demoted after such a battle, the other marshals also began to notice the narrow margins by which they were winning victories. It was only a matter of time before Napoleon’s miscommunications led to disastrous results for the marshals, their soldiers, and for France.

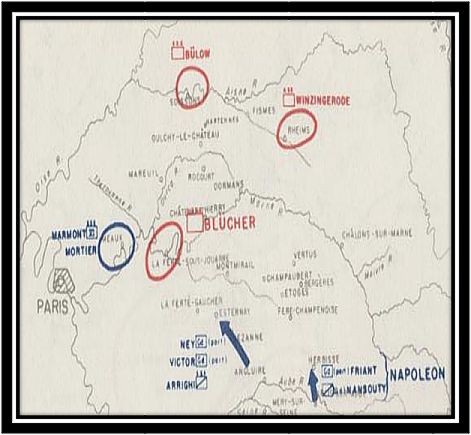

DEFEAT CREEPS IN, FEBRUARY-MARCH 1814

With his minor victories in February, Napoleon drove off the Allied armies, but he did not decisively defeat them. He still held the critical central position, with the Army of Silesia astride the Marne River to his north, while the Army of Bohemia was still on the Seine River to his south. In March, Napoleon repeated practically the same strategy he used in February, beginning with a strike against the still-recovering Prussians under Blücher. The Prussians were certainly in a vulnerable position as their main body was located between the Marne and Aisne Rivers. Having already succeeded in defeating the Prussians in early February, Napoleon felt he could destroy their army completely this time around. Instead, poor communication on his part would lead to a series of outright defeats against the Prussians and then against the Austrians. Napoleon still depended on his marshals for victory, but both the marshals under his direct command and those with their own commands were constantly misinformed or misdirected by their emperor. These miscommunications inevitably led to defeats against far larger Allied armies, and the marshals saw this failure to communicate plans effectively was no longer just preventing decisive French victories: it was costing France the war.

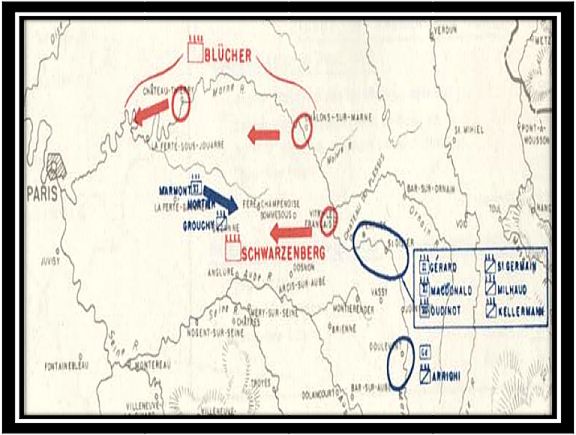

The Position of the Main Allied and French Formations

at the Conclusion of the First Part of the 1814 Campaign, February 24, 1814

Napoleon’s Advarnce Against the Exposed Positions of the Army of Silesia, February 27, 1814

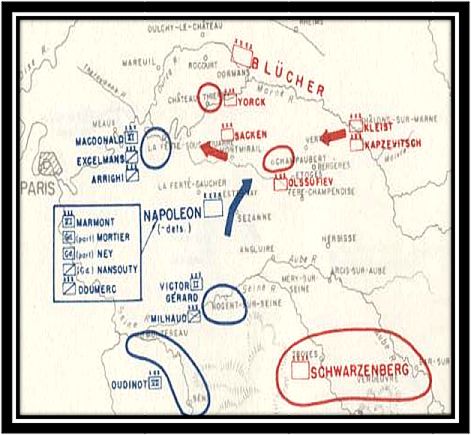

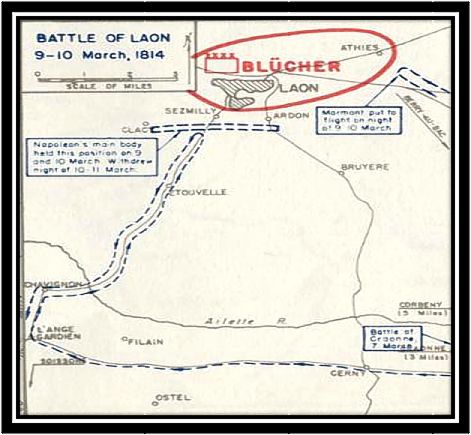

The marshals’ dependence on Napoleon’s communication led to a bloody defeat that drastically altered Napoleon’s campaign plan. First, he combined the corps of Mortier and Marmont with his main body, and crossed the Aisne. At Craonne on March 7, Napoleon launched a frontal attack against the Prussians and inflicted 5,000 casualties, forcing Blücher to retire from the battlefield. Blücher amassed his entire army on a ridgeline in front of Laon, strongly supported by a series of defended villages. Napoleon, with barely 40,000 men, decided on a two-pronged attack on March 9: Mortier and Ney would attack the Prussian right, while Napoleon presumed that Marmont’s Sixth Corps would attack the Prussian left when they reached the battlefield. But Marmont’s corps marched to Laon by a different road than the rest of Napoleon’s army, so when Marmont arrived on the field at 1:00 p.m., he was nearly five miles from Napoleon, and had not received any direct communications from the emperor in several days. In order to ensure that Napoleon really wanted Marmont’s 10,000-man corps to attack half of the Prussian army on a defended ridge, the marshal dispatched his corps of cavalry to remain in contact with the main body of the French army.

Battle of Laon, March 9-10, 1814

Marmont, seemingly desperate for orders from Napoleon, used up his cavalry screen to ensure he had a link with the emperor. His men attacked the village of Athies and achieved some success, but they spent the rest of the day camped on the battlefield. With no pickets or cavalry guarding the French position, Prussian cavalry attacked into Marmont’s rear at 7:00 p.m., and reported that there was an entire French corps isolated from Napoleon’s main force. Two entire Prussian corps attacked Marmont’s formation and routed it, forcing Napoleon to retreat from the battlefield, this time having failed to achieve even a small victory against the Prussians. While Marmont certainly bares the blame for not ensuring his men were well-guarded when they encamped for the evening, in truth he simply did not expect to face as large a Prussian force as he did when he reached the battlefield. Napoleon could not afford to leave an intact Prussian army operating in France, so he was forced to attack it, and called up all immediately available units to fight at Laon. When Marmont arrived at Laon, he saw a larger enemy army in a more concentrated area, and fatally dispatched his cavalry to keep his corps in contact with Napoleon. After the defeat Napoleon wrote to his brother Joseph, claiming that the Prussians would have evacuated Laon out of fear of a French attack, if not for the rout of Marmont, “whose behavior was that of an ensign.” It was bad enough that Napoleon’s lack of communication left Marmont isolated and forced him to dispatch his cavalry screen; for Napoleon to place the entire loss of the battle on Marmont’s shoulders seemed absurd to the man who had just watched his entire corps routed in a few hours. While Marmont was certainly willing to continue fighting against immeasurable odds to defend France, he was beginning to tire of being placed in poor positions by his commander, and he certainly did not expect to be criticized for a failure which arose out of Napoleon’s inability to communicate.

Advance of the Army of Bohemia on Troyes and Beyond,

while Napoleon Advances Against the Army of Silesia, March 5, 1814

If Napoleon had problems communicating with marshals under his direct command, he had even more difficulty relaying orders to his subordinates fighting along the Seine. With Victor no longer commanding an independent force, it was up to Oudinot and Macdonald to hold off the Army of Bohemia. Macdonald believed he was left in charge by Napoleon as the senior general in the sector, even though both men received their marshal’s baton in 1809 after Wagram. Napoleon initially wanted to relieve his fortresses at the beginning of March, a plan which caused a great deal of confusion to the marshals under his command, especially once Napoleon changed his plans without warning and attacked the Prussians instead. It was the same for Macdonald and Oudinot, who were led to believe that Napoleon would march east, relieve besieged French garrisons, and operate in the Allied rear, thus forcing Schwarzenberg to abandon his line on the Seine. Instead, Napoleon attacked the Prussians, and Schwarzenberg, free from concern of any sudden maneuvers on his flank or rear, concentrated his entire army against Oudinot’s corps. Oudinot was easily outflanked and forced to abandon Troyes, the key city to operations on the lower Seine, on March 4. Without a clear leader among them, Oudinot and Macdonald constantly disagreed with each other, and they acted independently of each other, rather than trying to work together to delay the Austro-Russian behemoth. In response to this disunity, Macdonald wrote that, despite the critical nature of their situation (the Seine River led all the way to Paris), neither he nor Oudinot had any “news from the emperor, though not because [they] had not sent him warning.” Napoleon’s marshals understood that he could concentrate his main army against only a certain enemy force at any one time, and that this would leave other areas more vulnerable to attack. In fact, this was true of all of Napoleon’s campaigns since 1796: concentrate individual corps against a certain element of the enemy’s force, and decisively defeat it before the enemy could attack one’s own weak points. But in 1814, the marshals far from Napoleon’s main force, and in command of such weak points, lacked the strength to hold off the Allied armies, and more importantly they lacked a clear outline of Napoleon’s strategy.

Neither Oudinot nor Macdonald could be expected to hold off the Army of Bohemia on their own, and without clear orders from Napoleon they were not really sure what to do once they retreated from Troyes. Napoleon was furious with the loss of the city, claiming he “left a splendid army and excellent cavalry at Troyes,” and the real failure was that “the souls [of his marshals were] wanting.” Napoleon blamed his marshals for derailing his plans, but he had never clearly told them his plans, even when they asked for specific directions. It was Napoleon’s inability to leave clear orders for his subordinates, to let them know what his own plans were, and to leave a clear commander in charge that forced Oudinot and Macdonald to lose Troyes and retreat forty miles to the northwest. If Troyes was vital to the entire French defensive position, then Napoleon’s orders needed to include a command to hold the city at all costs. He did not do this, so the marshals felt Troyes could simply be abandoned in the face of overwhelming Allied superiority, thereby trading space for time. This retreat, brought on by Napoleon’s inability to clearly organize his orders, forced Napoleon to abandon his campaign against the undefeated Prussians. On March 16, Napoleon fatefully decided to march his main force south to fight the advancing Austro-Russian army. His poor communication had already led to individual French units being mauled against the Prussians; Napoleon was forced to leave the intact Prussian army in his rear, and attack an even larger Allied army that was advancing freely on the Seine because Napoleon had failed to provide clear orders to Macdonald and Oudinot.

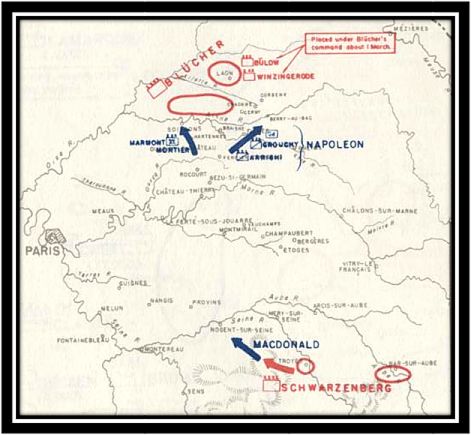

Napoleon’s plan to concentrate against one enemy army in the Allied coalition could only work if his marshals knew when and where to concentrate. Having failed to defeat the Prussians, Napoleon also lacked the strength to defeat the larger Austro-Russian army. With barely 28,000 men under his command, he suffered another defeat at Arcis-sur-Aube on March 20 against an Allied army of nearly 100,000 men. Napoleon decided to move to the northeast, setting up the decisive final days of the campaign. Marmont and Mortier had 25,000 men to defend the approaches to Paris against the Army of Silesia. Napoleon, with Ney, Macdonald, and Oudinot under his own command, was to the east of both of the main Allied armies. Although Napoleon felt this position would be advantageous to his operations, it proved disastrous to his strategic plans. Napoleon, seeing that his army was no longer a match for Allied numbers, decided to try and raise the size of his own force. But as the Allies drew closer to Paris, Napoleon continued to conduct operations without informing his marshals of what his plans were. They were either left to fend for themselves against the Allied advance, or Napoleon simply ignored them. Even if Napoleon could win battles on his own, he could not be everywhere at once, and he needed his marshals to perform well if he wanted to win the campaign. But Napoleon’s employment of rapid corps marches to concentrate against superior Allied forces would only succeed if his marshals lived up to his expectations. While some marshals were capable of operating under an overall strategic framework with no clear operational direction, these were men like Soult and Davout, who held independent commands in southern France and Germany, respectively. Marshals like Marmont and Macdonald, who Napoleon picked to fight in France in 1814, were less capable of independent command, and so Napoleon needed to clearly lay out his plans to ensure they operated according to his strategic vision. He failed to do so, and so his marshals could not help but fail against the overwhelming Allied armies.

THE MARSHALS ABANDONED, LATE MARCH 1814

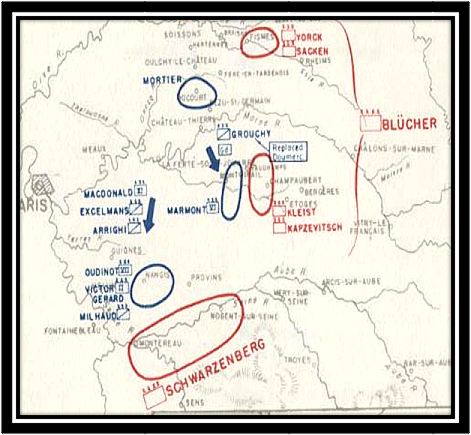

From March 20 until March 31, 1814, three different armies on both sides were operating between the Rhine River and Paris. First were the combined corps of Marshals Marmont and Mortier, 25,000 men defending the approaches to the French capital. Immediately to their east were the two main Allied armies, with nearly 180,000 men between them. Finally, east of this force was Napoleon’s main army of some 30,000 troops. Napoleon, having repeatedly failed to bring either Allied army to a decisive battle, decided he needed greater troop strength before continuing his campaign. To accomplish this he wanted to head east and relieve his besieged garrisons on the Rhine, while also severing Allied lines of communications before they could march on a weakened Paris. But Napoleon’s orders to Marmont and Mortier were contradictory and based on erroneous intelligence, forcing both of these men to constantly march and countermarch in the vicinity of massive Allied armies. When Paris itself was finally threatened, Napoleon returned to his capital, not having had time to relieve his garrisons and raise his armies. The end result of Napoleon’s inability to direct his subordinates was that Paris fell to the Allies, and the marshals, tired of this lack of communication, finally turned on the Emperor.

Advance of the Allied Armies on Paris,

while Napoleon Advances East Towards the Rhine, 24 March, 1814

Napoleon relied on Marmont and Mortier to keep the Allies from striking at Paris while he moved east, but he simply kept them confused of his real strategy for the campaign. While he moved south to strike the Austrians in mid-March, he ordered Marmont to Fismes to guard the road to Paris with Mortier and “dispute every inch of ground.” But as soon as the two corps arrived in Fismes, they received counter-orders to force-march 40 miles southeast to Chalons. Napoleon, concentrating most of his forces against Schwarzenberg on the Seine, seemed unsure what exactly he wanted to do with these two extra corps while he sought a decisive engagement with the Army of Bohemia. While clear communication was vitally important, constantly sending conflicting orders to his marshals was no way of ensuring they understood his plans. At first, they believed Napoleon wanted them to defend Paris, but as soon as they were in a position to do so (at Fismes), they were told to march to a completely different location closer to Napoleon’s main force. Recognizing that their corps lacked the strength to defend Paris on their own, Napoleon was willing to sacrifice Paris in return for a concentration of force east of the main Allied armies. Unfortunately, none of these plans took into account Blücher’s Army of Silesia, which Napoleon should have known was near Marmont and Mortier. The two marshals, rather than driving southeast to Chalons, were instead driven out of Rheims by the Prussians on March 19, and forced to retreat back to Fismes. Napoleon did not take into account the operational area of the Prussians when ordering Marmont and Mortier to join him, resulting in another defeat for these two marshals.

Instead of altering his plans to allow space for the operations of Allied armies close to his own forces, Napoleon stubbornly continued to unite his entire force. On March 21, following his defeat at Arcis-sur-Aube, Napoleon ordered Marmont and Mortier to move to Vitry, meaning they would have to head south, cross the Marne, and then head east to rejoin his main body. Unfortunately, Napoleon once again failed to include a critical piece of information in his orders: both Allied armies were directly in between him and the two marshals. Although Napoleon clearly communicated his goal of increasing the size of his army, he failed to communicate vital information about enemy troops in a particular area. After marching away from the Prussians at the beginning of the month, retreating east after losing to the Austrians, and ordering Marmont and Mortier to defend Paris, Napoleon was well aware of where all these forces were generally located in France. Marmont and Mortier, caught between two Allied armies, suffered a defeat at Bussy l’Estree. Once again, poor orders on Napoleon’s part led to a defeat his marshals lacked the strength to recover from. Additionally, Allied troops surrounded and destroyed a 4,000-strong National Guard division under General Pacthod that was marching to reinforce Marmont at La Fere Champenoise on March 25. Thus, Napoleon’s miscommunications were leading not only Marmont and Mortier to disaster, but also preventing them from receiving desperately needed reinforcements, since all of these formations were being ordered into the middle of two Allied armies. The marshals were no longer simply losing battles; they were being routed, and in close proximity to the French capital they were defending.

Meanwhile, Napoleon’s main army suffered from not knowing exactly where it was going or what its goal was. Ostensibly trying to head east to the Rhine to relieve the large French garrisons isolated there, Napoleon failed to accomplish even this modest goal. After losing at Arcis-sur-Aube, the main French army moved northeast towards Vitry, and found it defended. Marshal Macdonald, seeing that the town was strongly defended, argued that Vitry could only have a large garrison if the Austrian army was nowhere near the town; in other words, Vitry’s garrison was simply defending Austrian lines of communication, and not part of the main Austrian field army. This meant that the Allies were moving west, and thus moving towards a Paris barely defended by recently defeated French troops. Macdonald was exactly right: on March 24, the Allied armies, tired of playing cat and mouse with Napoleon and eager to end the campaign, finally began marching west on Paris while Napoleon stayed at Vitry. Whereas with Marmont and Mortier Napoleon had failed to communicate the location of the two main Allied armies, with the marshals under his direct command Napoleon constantly switched his orders to his subordinates. First, he erroneously believed that the Austrians were actually retreating to the Rhine, meaning his army at Vitry would be ideally placed to cut off and destroy them. Then, deciding to resume his advance on the Rhine, he moved east, running into an Allied rear guard under General Ferdinand Wintzingerode which he defeated at St. Dizier on March 26. The general movements covering the nearly 20 miles between Vitry and St. Dizier were as follows: Napoleon was near Vitry on March 22, near St. Dizier on March 23, marched away from St. Dizier on March 24, returned to it on March 26 to fight Wintzingerode, and marched back near Vitry on March 27. Such conflicting orders, a characteristic of Napoleon’s communications during this campaign, prevented his marshals from either decisively defeating Wintzingerode or from concentrating on and capturing Vitry. Thus, Napoleon’s main army was neither fighting the main Allied armies, nor destroying the small forces it did face, nor capturing enemy-occupied towns, and certainly not relieving garrisons on the Rhine: in short, Napoleon’s orders to his marshals were achieving nothing. While orders that led to half-victories and defeats were certainly not popular among the marshals, these professional officers were probably less content with orders that accomplished nothing at all.

On March 27, Napoleon finally learned that, while he was marching east, the Allies were instead marching west against a barely defended Paris. With the Allied armies much closer to Paris than he was, Napoleon decided to change his strategy one more time, and decided that Paris needed to be defended. Macdonald argued that by marching back west, Napoleon would accomplish neither of his primary goals: he would not have raised enough soldiers from his garrisons to increase his army’s size, nor would he make it to Paris with a large enough force to defend it from the impending Allied onslaught. Napoleon ignored Macdonald and raced west to save Paris. While it was Napoleon’s prerogative to ignore advice from subordinates, it was easy to see why Napoleon’s orders to his commanders were so confusing when he constantly revised his strategy. The marshals under his direct command, unsure whether Napoleon wanted to achieve a military or political goal, were either left in the dark or just misinformed about what Napoleon really wanted to accomplish.

The climax of the 1814 campaign occurred with Marmont and Mortier defending the approach to Paris from the Allied advance. Even as late as March 29, the people of Paris did not believe they were facing more than 30,000 Allied troops on the outskirts of their city. On that same day, Marmont and Mortier arrived in the city, with only 9,600 men left under their command. The regime in Paris was left under the command of Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon’s brother, and Marie Louise, Napoleon’s wife, while the Emperor was in the field. On March 16, Napoleon, before marching east of the Austrians and thus cutting off direct communication with Paris, informed Joseph that he would be out of touch for some time. Napoleon left clear instructions to Joseph on whom and what to evacuate should Paris come under threat from the enemy. Thus, Napoleon knew his maneuvers put Paris at risk and that he would be cut off from the government of the city, and so he left clear orders to follow in case the Allies captured the city. Unfortunately, Napoleon was never quite so direct with Marmont and Mortier, so they did not know how hard a fight they were expected to put up for the French capital. Marmont, taking charge of the defense of the city, immediately inspected the Belleville heights when he arrived, because he had never before studied the area around Paris as a potential military position. This made sense because, over the last three months, Napoleon’s strategy focused entirely on either defeating the Allied armies, or increasing the size of the French army. Thus, while three months was plenty of time to ensure Paris was strongly defended against any possible attack, it never figured into Napoleon’s strategy as a place that needed defending, and so Marmont was neither ready to nor capable of defending it. Although Napoleon was marching at full speed to return to Paris to save it from capture, Marmont was still operating under the idea that Napoleon’s primary goal was restoring the French army to a credible size. With this in mind, he put up a tough fight on March 30 in front of Paris on the heights of Montmartre, then that evening he concluded an armistice that allowed his soldiers to withdraw peacefully if he surrendered Paris.

While Marmont saved the bulk of the regular troops defending Paris, he had lost the capital, and Napoleon was infuriated that he missed reaching his capital just a few hours before it surrendered. He waited several days near Fontainebleau south of Paris, gathering his forces in preparation for a strike on the Allies. While neither Napoleon nor his marshals argued that the loss of Paris was a disaster, Napoleon still saw an opportunity for victory. In fact, the Allied armies were concentrated in Paris, a massive city known for its turbulent, anti-foreign population, and Allied supply lines stretched all the way back to the Rhine. Meanwhile, Napoleon, for the first time in three months, had every marshal he started the 1814 campaign with under his direct command, with all their corresponding forces. In effect, the Allied armies were tied down occupying a large, unfriendly capital divided in two by the Seine River, while their supply lines stretched hundreds of miles. In contrast, Napoleon’s supply lines were extremely short, he was free to maneuver wherever he wished, and he finally achieved a true concentration of his army. With such advantages, Napoleon prepared for a strike against the French capital. Unfortunately for the Emperor, on April 3 Marshals Ney, Macdonald, Oudinot, Berthier, and Lefebvre mutinied, and refused to contemplate carrying the war on any further. They believed Napoleon completely botched the 1814 campaign, and could no longer carry out this futile campaign.

The marshals were still willing to fight to defend France even with the overwhelming odds facing her when the Allies crossed the Rhine in January 1814. But during three months of difficult fighting, the marshals repeatedly found themselves on the receiving end of poor communication. They were tired, not of war, but of Napoleon’s continued inability to clearly specify what he wanted of them. Such miscommunication prevented victories from being truly decisive and, as the campaign wore on, resulted in defeats of greater magnitude. While Napoleon was the commander of the French armies, the corps that marched, countermarched, won half-victories, and suffered disastrous defeats were led by the marshals. It is ironic that by April 1814, when Napoleon finally achieved a true concentration of force close to a stretched out Allied army vulnerable to attack, the marshals were no longer willing to follow him. They did not believe Napoleon could win even with some type of operational advantage: the only thing the marshals could be sure of was that any order from Napoleon to attack the Allies in Paris would be fraught with unclear directives, and their own men would suffer the brunt of the fighting regardless of the result. Two days after the mutiny at Fontainebleau, Marmont’s corps defected to the Allies. Marmont’s betrayal certainly shook Napoleon more because it involved the loss of a large part of his army. Marmont’s betrayal was of a greater magnitude than the other marshals because he suffered the most from Napoleon’s miscommunication. Whether it was his corps being routed at Laon, or being ordered to maneuver in between Allied armies, or being forced to defend Paris with no orders from the emperor, Marmont and his men bore the consequences for Napoleon’s failures. Marmont was also tired of being blamed by Napoleon for failing to discern the emperor’s strategy and for failing to hold up the Allied behemoth. With neither the strength to stand up to the Allies nor clear orders on what to do with his men, Marmont felt he did everything he could to save Paris, fighting until the capital itself was under fire and with little hope of reinforcements. When Napoleon finally did arrive and wanted to attack Paris, a city which Marmont defended almost single-handedly, the marshal finally had enough and defected.

CONCLUSION

Napoleon’s marshals were the heart of his army structure. The corps system Napoleon invented could not function without intelligent, independent commanders capable of taking his overall strategy and translating that into efficient military operations. But by 1814, Napoleon no longer communicated so effectively with his subordinates. The result was a series of half-victories, contradictory maneuvers, and outright defeats that slowly infuriated the Napoleonic marshalate. Often times, Napoleon left small corps under his marshals while he took his main army far away to try and seek a decisive battle against much larger Allied armies. In February and March, Napoleon targeted a different army for destruction no fewer than four times. This meant that every time a new target was chosen, the main French army marched rapidly to a different part of France during the winter of 1813-1814, while relatively small forces remained to hold off the other Allied army. Instead, the Allies constantly kept pressure on the French, forcing Napoleon to cut short his operations and move to whatever sector was most threatened.

The victories of February 1814 demonstrated that the marshals were certainly not weary of fighting wars, as they displayed a great deal of vigor and intelligence in defeating much larger Allied armies. As long as Napoleon was leading them to victory, the marshals were also unwilling to blame him for any of France’s problems: instead, they felt the fastest way to ensure peace was to decisively defeat the invading Allied armies. Unfortunately, none of these victories conclusively destroyed either the strength or the morale of either Allied army. Napoleon’s miscommunications ensured that all of these victories took a heavy toll on a France no longer capable of sustaining heavy casualties, while also preventing the destruction of the Allied invaders. In March, the routed Allied armies, resupplied and reinforced, returned in force, and Napoleon, still on the offensive, suffered far greater casualties in a series of poorly coordinated attacks against the Prussians and the Austrians. He blamed his marshals for these failures, with the result that the marshals were often castigated for Napoleon’s mistakes, or that they saw their own corps cut up from being put in a poor position. This trend only grew worse in the last weeks of March, when Napoleon boldly struck out east away from the Allied armies, leaving them to face only a tiny fraction of the total French army, and cutting that fraction up as the Allies approached and captured Paris.

The marshals were promoted from the ranks of the French army by Napoleon himself. He gave them wealth, social status, and key military commands. They were a mixed bag of officers with varying strengths and weaknesses, but they nevertheless constituted the cream of Napoleon’s general officers. They certainly did not get soft and content after being laden down with so many rewards: rather, their tenacious defense of France against such overwhelming odds proved that the marshals were still willing to fight for their country, and under Napoleon’s orders. If the marshals were truly weary of war, they would have abandoned Napoleon long before the Allies entered Paris. Nevertheless, the 1814 campaign saw a growing dissatisfaction among the marshalate. They were professionals, and general officers made unique only by distinction of holding a marshal’s baton. They were the true heart of Napoleon’s corps system, and this system only truly fell apart in 1814, where Napoleon attempted to exert complete control over his forces, but did so with unclear orders and poor directives. At one point in the campaign, he even believed his marshals’ souls were “wanting,” and that was why they could not see his orders through to victory. In reality, it was Napoleon’s orders that proved wanting, and so he found himself at Fontainebleau with only himself to blame for driving his once-loyal marshals to turn on him.

To make this article easier to read, we have removed the footnotes and list of sources from the version shown here. To see a PDF version of this paper complete with footnotes, appendices, and bibliography, click here.

This article is copyright © 2009 Claudio Innocenti.

Reprint right granted to the The Napoleonic Historical Society by the author.