Collecting Napoleonic Militaria

By Sheperd Paine

Of all Napoleonic collectibles, few combine physical beauty with

historical significance as spectacularly as the military relics

of that era. In addition to being beautiful objects in their own

right, these splendid survivors of the battlefields of the Empire

were not just "eyewitnesses" but actual participants in

some of the most dramatic events of modern history.

Most people assume that all the tangible remnants of Napoleon and his

Empire are locked up in museums, and never realize that it is possible

to own genuine relics of the events that so stir our imagination.

Yet these items are not only available, but remain within many collectors’

financial reach.

Most people assume that all the tangible remnants of Napoleon and his

Empire are locked up in museums, and never realize that it is possible

to own genuine relics of the events that so stir our imagination.

Yet these items are not only available, but remain within many collectors’

financial reach.

It is true that objects can never actually speak, but a careful study

of them can reveal many secrets about their past. More significantly,

to the receptive mind they can communicate on a subtler level as

well. Holding in one’s hand an object that was actually "there"

can impart a deeper intuitive understanding of historical events

than can ever be derived from just reading about them.

Some relics of the Napoleonic period are extraordinarily expensive; others

are not. While a collector’s tastes are always tempered by the depth

of his or her pocketbook, there remains a wide selection of Napoleonic

items within comfortable reach of a determined collector on a budget.

It is beyond the scope of thbis short article to provide a detailed

guide to Napoleonic Militaria. A more realistic goal is pass along

some accumulated wisdom from experienced collectors — things that

are not always found in books, but are essential knowledge for beginning

and advanced collector alike. If you have been collecting

only a short time, nearly all of this material will be new to you.

If you have been collecting for a few years, much of it will not.

And if you have been a collector for many years, by all means drop

us a line — perhaps we can learn something from you!

Knowing What to Look For

If you want to collect Napoleonic militaria in the United States, it pays to know your subject. American antique dealers have little knowledge of French history and are quick to proclaim anything with an eagle or an N on it as Napoleonic. Many objects offered as relics of the First Empire of Napoleon I are actually from the Second Empire of Napoleon III (1848-1870), and it is important for collectors to know the difference.

First Empire Eagle

Second Empire Eagle

Medals and Decorations

Napoleon believed that awards were an important inspiration to his troops, and accordingly showered them with a variety of awards.

The most important of these, and the most sought after today, is the

Legion of Honor. Since this decoration continued in use by subsequent

regimes (and is still awarded today), it is important to be able

to tell the First Empire types from the ones that followed. First

Empire crosses are generally divided into four successive types:

1) with no crown, 2) with a fixed crown 3) with a swivel crown,

and 4) with a swivel crown and balls on the points of the cross.

The later model closest in appearance to the First Empire types

was naturally that of the Second Empire, which is easily distinguished

by the eagles on the crown. Restoration models (1815-1830) have

King Henri IV on the center, July Monarchy types (1830-1848) have

Napoleon, but crossed flags on the back, and the post 1870 version

has a green enameled wreath in place of the crown.

The most important of these, and the most sought after today, is the

Legion of Honor. Since this decoration continued in use by subsequent

regimes (and is still awarded today), it is important to be able

to tell the First Empire types from the ones that followed. First

Empire crosses are generally divided into four successive types:

1) with no crown, 2) with a fixed crown 3) with a swivel crown,

and 4) with a swivel crown and balls on the points of the cross.

The later model closest in appearance to the First Empire types

was naturally that of the Second Empire, which is easily distinguished

by the eagles on the crown. Restoration models (1815-1830) have

King Henri IV on the center, July Monarchy types (1830-1848) have

Napoleon, but crossed flags on the back, and the post 1870 version

has a green enameled wreath in place of the crown.

Legion of Honor collectors will be quick to point out further complications:

that the centers and other parts are easily interchanged, that genuine

First Empire crosses sometimes had their centers replaced so they

could be worn during the Restoration, and that unscrupulous dealers

have been known to mount Second Empire centers on Restoration crosses,

which have a crown closer to the First Empire type. Still, the most

common error is to mistake a Second Empire cross for a First Empire

one, and if you can avoid that trap, you can buy with a modest degree

of confidence. Prices for First Empire Legions of Honor vary with

the grade and metal content. All chevalier crosses are solid

silver, and many of the officier crosses are solid gold.

The fourth model cross, with the balls on the points, is the most

common and a chevalier‘s cross can usually be found for $800-1500,

depending on the amount of enamel damage. If you are offered a perfect

specimen at the low end of that range, be wary. As in other aspects

of life, if something appears too good to be true, it usually is.

Legion of Honor collectors will be quick to point out further complications:

that the centers and other parts are easily interchanged, that genuine

First Empire crosses sometimes had their centers replaced so they

could be worn during the Restoration, and that unscrupulous dealers

have been known to mount Second Empire centers on Restoration crosses,

which have a crown closer to the First Empire type. Still, the most

common error is to mistake a Second Empire cross for a First Empire

one, and if you can avoid that trap, you can buy with a modest degree

of confidence. Prices for First Empire Legions of Honor vary with

the grade and metal content. All chevalier crosses are solid

silver, and many of the officier crosses are solid gold.

The fourth model cross, with the balls on the points, is the most

common and a chevalier‘s cross can usually be found for $800-1500,

depending on the amount of enamel damage. If you are offered a perfect

specimen at the low end of that range, be wary. As in other aspects

of life, if something appears too good to be true, it usually is. The campaign medal for the Napoleonic wars is disappointing. Called the St. Helena Medal, it was not awarded until 1852, by which time many of the most deserving recipients were long dead. Still, thousands were given out, and without a name attached to them they rarely bring more than $50.

A quick mention should be made of foreign decorations as well. Nearly all counties involved in the Napoleonic wars gave campaign medals to their participants, usually in silver for officers and bronze for other ranks. The British, curiously enough, instituted the Waterloo medal immediately after the battle for all ranks present, but waited until 1848 before awarding a similar medal (with bars on the ribbon for battles in which the recipient took part) to veterans of the Peninsula. The wonderful feature of British medals is that the name and regiment of the recipient were officially engraved on the rim. This makes it possible to acquire a Waterloo medal knowing that it was awarded to (and actually worn by) a man who charged with the Scots Greys or defended Hougomont with the Guards. The officalmedal rolls are still on file at the Public Records Office in London, allowing you to confirm the recipient.

Swords

Swords are probably the most common Napoleonic relics. Fortunately, the type most sought after by beginning collectors is also the one most frequently encountered.

The Emperor’s cuirassiers were the scourge of the European

battlefields and their long straight broadswords saw almost continuous

service for over a century, which ensured that many survived. There

were minor changes in design as the years went by, and new and old

hilts, grips, and blades were combined and recombined as the needs

of the service required. Blades made in 1812 were still being carried

on the battlefields of 1914! This process of combining new and old

parts means that an 1812 date on a blade is no indication that the

other parts are of the same period. The classic First Empire cuirassier

sword (see the illustration at left) can be distinguished by a number

of features: the balls at the base of each branch of the basket,

a smooth unchanneled base for the guard, and a plain cylindrical

pommel cap with no rim around the top. The wire made only 11 turns

around the grip, not 16 as on later patterns.

The Emperor’s cuirassiers were the scourge of the European

battlefields and their long straight broadswords saw almost continuous

service for over a century, which ensured that many survived. There

were minor changes in design as the years went by, and new and old

hilts, grips, and blades were combined and recombined as the needs

of the service required. Blades made in 1812 were still being carried

on the battlefields of 1914! This process of combining new and old

parts means that an 1812 date on a blade is no indication that the

other parts are of the same period. The classic First Empire cuirassier

sword (see the illustration at left) can be distinguished by a number

of features: the balls at the base of each branch of the basket,

a smooth unchanneled base for the guard, and a plain cylindrical

pommel cap with no rim around the top. The wire made only 11 turns

around the grip, not 16 as on later patterns.

Whatever the model or style, all of the enlisted pattern swords used during the First Empire were set forth in regulations and rigorously inspected. A great boon to collectors is that the month, year and place of manufacture was etched along the spine of the blade (a practice that continues on French weapons to this day) and each part was stamped with the initial of the controller who supervised its manufacture. Virtually all First Empire blades were made at Klingenthal, and are so marked. The light cavalry types used during the First Empire were replaced with a new model in 1822, making them somewhat scarcer than the Cuirassier type. First Empire enlisted scabbards were lined with wood, making both metal and leather versions very thick, almost round and often as much as an inch across; post-empire scabbards were much thinner. The brass-hilted infantry sword remained in use for several decades afterward and was widely copied by other countries, so these must be approached with caution. Without an arsenal mark and date on the top of the blade, the sword you are thinking of buying is probably not French, however much you might want it to be.

The cavalry and infantry of the Imperial Guard carried their own distinctive models, and the few surviving examples are in great demand today, and correspondingly expensive. I saw an Imperial Guard light cavalry model for sale in Paris a few years ago for over $5000, a price usually reserved for deluxe officers’ swords. The swords for the two carabinier regiments are even rarer than those of the Guard.

In contrast to the enlisted models, there were few regulation patterns for officers’ swords. This was the golden age of the military cutler, and a bewildering variety of blades survive to this day. Still, there were customary patterns for different types of service, and most swords followed these general guidelines. Officer’s blades during this period were nearly always decorated with blued and gilt designs for about a third of their length, a practice that was replaced with frost etching almost immediately afterwards. This means that if you come across a sword with the remains of this blued and gilt decoration, the chances are that it is a First Empire type, if not necessarily French. Similarly, officer’s swords often had checkered walnut or ebony grips, a practice that also passed out of fashion with the fall of the Empire, making a sword with these grips almost certainly a First Empire example. Light cavalry and infantry officer’s swords are not uncommon and can sometimes be found at gun shows, although examples in really fine condition are harder to find.

The deluxe parade swords, of which many fine examples survive, represent

the pinnacle of the sword cutler’s art, and bring high prices on

any market. Perhaps the most desirable are the "swords of honor"

awarded to private soldiers and NCOs for heroism before the institution

of the Legion of Honor in 1804. These were often made at Versailles

under the direction of Nicholas Boutet, and are engraved with the

name and regiment of the recipient.

The most common swords are not terribly expensive, as edged weapons

go. Good enlisted models can often be found for $750-1000, and the

plainer officers’ swords in average condition are not much more

than that.

Firearms

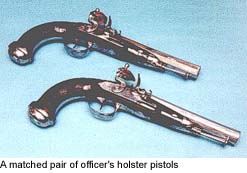

Enlisted firearms, like swords, were well regulated and inspected. The standard infantry arm was the An 9 musket, a slightly simplified version of the 1777 model; the troops nicknamed it the "five foot clarinet." The cavalry carried carbines and a pair of pistols in the saddle holsters. All of these arms are available to collectors today, at prices ranging from $750 to $2000. Only a handful of Imperial Guard muskets, with their characteristic brass furniture, have survived and rarely appear on the collectors’ market. Mounted officers also carried a pair of pistols in their saddle

holsters, but these, like their swords, were privately purchased

and followed no regulation model. The workmanship on these matched

pairs is often exquisite, yet they are often considerably less expensive

than their glamorous cousins, the cased dueling pistols.

Mounted officers also carried a pair of pistols in their saddle

holsters, but these, like their swords, were privately purchased

and followed no regulation model. The workmanship on these matched

pairs is often exquisite, yet they are often considerably less expensive

than their glamorous cousins, the cased dueling pistols.

The ultimate firearms of the First Empire period were undoubtedly those produced by the Manufacture de Versailles, under the direction of Nicholas Boutet. Boutet has often been called the "Michelangelo of gunsmiths," because of the beauty of the decoration on his presentation arms, but a comparison to Stradivarius might actually be more appropriate; his plainer pistols, while still elegant in their lines, have an astonishing balance and mechanical sophistication far exceeding other arms of the period.

Headdress

The variety of headdress worn by the officers and men of the Grande Armée was awesome to behold: shakos, brass and iron helmets, bonnets de police, bearskins, and colpacks, not to mention the famous cocked hat of the Emperor himself.

For this reason, these items have been sought by collectors for over a hundred years.

There is not enough space here to discuss Napoleonic headgear in

any detail. Instead, I will limit my comments to some general advice.

For this reason, these items have been sought by collectors for over a hundred years.

There is not enough space here to discuss Napoleonic headgear in

any detail. Instead, I will limit my comments to some general advice.

Learn as much as you can not only about Napoleonic helmets and shakos, but about those of subsequent regimes as well. These are often passed off as First Empire pieces, and if you can recognize them, you are far less likely to be taken. For example, nearly all of the metal helmet crests made after the fall of the Empire were decorated with a series of inverted "teardrops" along the sides; these were never found on First Empire helmets. Study the small but important characteristics of First Empire construction: the "bull Durham bag" lining, the embossed patterns on the leather visors, the weight and thickness of the brass stampings. Take advantage of every opportunity to hold pieces in your hand; by learning the "feel" of a piece — its weight, texture, and flexibility — you can educate your hands to distinguish what your eyes might overlook.

Uniforms and Insignia

Uniforms are almost impossible to find in decent condition, although they are not outrageously expensive when they do turn up. Accessories, such as epaulettes, are more common, but examples in really good condition are much rarer. Metal insignia, such as shako and cartridge box plates, buttons, gorgets, and belt plates turn up fasirly frequently. Most are stamped in brass or iron (not tin), but cartridge box and belt plates were usually cast. Officer’s items were much more finely detailed, and nearly always gilt (gold plated). The gilding process used at the time was called "fire-gilding": a mercury-gold mixture was applied to the object and the mercury burned off in a furnace, leaving a rich deposit of gold on the surface. Because it was brushed on, fire-gilding coated only the front of the object — the back should be tarnished copper. If you find a piece that is gilt on both sides, it has been electroplated, a process unknown until the 1880s. Buttons are fairly common, and can be an inexpensive form of collecting

that takes up little space. Buttons of the period were generally

flat, stamped in one piece with a loop soldered on the back. Revolutionary

period officer’s buttons were often stamped in thin metal (silver

or gilt) mounted on a wood or bone backing. Officer’s buttons of

the Empire period were of a flat, two-piece construction and are

characterized by a series of concentric bullseye rings on the back.

The domed hollow military button we are familiar with today did

not become common until after the empire.

Buttons are fairly common, and can be an inexpensive form of collecting

that takes up little space. Buttons of the period were generally

flat, stamped in one piece with a loop soldered on the back. Revolutionary

period officer’s buttons were often stamped in thin metal (silver

or gilt) mounted on a wood or bone backing. Officer’s buttons of

the Empire period were of a flat, two-piece construction and are

characterized by a series of concentric bullseye rings on the back.

The domed hollow military button we are familiar with today did

not become common until after the empire.

Gorgets were gilt crescents worn at the throat as a badge of rank by officers. French officers wore gorgets until the fall of the Second Empire in 1870. As a result, Second Empire gorgets are often advertised as First, but if one pays attention to the differences in the eagles as outlined above, the chances of being taken are greatly reduced.

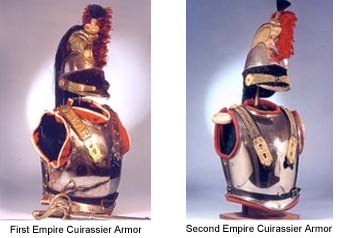

Armor

Perhaps the most striking survivors of Napoleon’s Grande Armée are the cuirasses and helmets of his heavy cavalry. A cuirass and helmet set is the dream of nearly every Napoleonic militaria collector. But care must be taken — the cuirassiers and carabiniers

of subsequent eras all wore similar equipment, and cuirasses and

helmets of these later periods are often offered as First Empire

pieces. Genuine cuirasses of the Napoleonic period are much rarer

than their successors, but they are easy to identify if one knows

what to look for. First Empire cuirasses were distinctly pot-bellied

in shape, had rivets all the way around (generally 28 of them, but

the number may vary slightly), and were narrower at the shoulders

than at the waist when seen from the front. The cuirasses of later

periods were more heroically shaped, with wide shoulders and narrow

waist, and had only five rivets. Napoleon III’s Guard cuirassiers

also had rivets all around, but their cuirasses were of the later

wasp-waisted shape. First Empire cuirassier sets were secured

by scale-covered leather straps over the shoulders, while the carabiniers

had chains instead of scales. Chains were used on all cuirasses

after 1816.

But care must be taken — the cuirassiers and carabiniers

of subsequent eras all wore similar equipment, and cuirasses and

helmets of these later periods are often offered as First Empire

pieces. Genuine cuirasses of the Napoleonic period are much rarer

than their successors, but they are easy to identify if one knows

what to look for. First Empire cuirasses were distinctly pot-bellied

in shape, had rivets all the way around (generally 28 of them, but

the number may vary slightly), and were narrower at the shoulders

than at the waist when seen from the front. The cuirasses of later

periods were more heroically shaped, with wide shoulders and narrow

waist, and had only five rivets. Napoleon III’s Guard cuirassiers

also had rivets all around, but their cuirasses were of the later

wasp-waisted shape. First Empire cuirassier sets were secured

by scale-covered leather straps over the shoulders, while the carabiniers

had chains instead of scales. Chains were used on all cuirasses

after 1816.

Copies and Fakes

Copies and fakes have been around for a long time, so long, in fact, that some of them qualify as antiques in their own right. Copies are replicas made and sold as such, while fakes are made to deceive the buyer. The trouble with copies is that yesterday’s copies often become today’s fakes.The best copies and fakes are extremely difficult to detect. In fact, the very best have never been detected at all, being accepted as genuine by beginner and expert alike. That said, there is no point in being paranoid about the situation. A bit of familiarity with the copies currently on the market will invariably stand you in good stead, and as you gain experience in the marketplace, your instincts will become sharper.

The most common copies seen today are the cuirassier and light cavalry swords being made in Pakistan. They are very good copies, but most lack the inspector’s proof marks found on original swords. Hold the sword by the grip and hold it out to feel the balance, If the point drops too quickly, watch out — the copies are always blade-heavy. Another good trick is to sight down the length of the blade: if the surface is rippled and looks hand-forged, it was probably made in Pakistan. The original swords were ground on giant wheels, leaving slight irregularities but not a rippled finish. Copies of officers’ swords have been made for some years in Eastern Europe. Their appearance is often quite convincing, but they are usually of the fancier style with foliate designs on the hilts. Swords of this quality were invariably gilt, and while the gilding is often rubbed off genuine specimens, traces will always remain in the little recesses. The fakes are not gilded at all, and the lack of gilt in the little nooks and crannies is an important warning sign.

Some fine examples of reproduction headgear were made for the centennial in 1904, and with 90 year of age on them these can often fool the unwary collector. But if you have done your homework, you should be able to spot the differences in construction.

Shako plates are known to have been struck from original dies, but the ones you are most likely to encounter in this country are those which were made for Bremner Jackson, a leading collector in the 1960’s. He planned to sell reproduction shakos, but never got farther than having the dies made and a few examples of each type struck. There was a wide variety, ranging from lancer czapska plates to shakos for the Guard and line. The plates are lighter and thinner than the originals, and the 1812 models are easily distinguished by the "spaghetti" pattern of feathers on the eagle’s chest.

Research

Books and museums are your best source for information. Do your homework and read everything you can on your subject. The surest way to be disappointed with your purchases is to rely on what the person trying to sell it tells you. A short "basic library" for the collector is listed at the end of this article. Take the time to build a photo reference file. The museums in France are excellent and allow photography without a flash. Comparing objects you hope to buy with photos you have taken in museums is the surest way to keep from getting stung.

Care and Cleaning

There are several approaches to the care and cleaning of military antiques. The most conservative is to do no cleaning at all, leaving the pieces in the state in which they were found. The opposite end of the pole is to refinish everything to "as new" condition. I personally favor a moderate approach, restoring items to the condition in which they were kept by the person who wore them. This means cleaning and polishing the brass, but leaving untouched the wear and tear that comes from active service. Such damage often tells a tale in itself. Sword scabbards, for example, are frequently dented along the lower right side of the scabbard, where they banged against the owner’s spurs. Taking these dents out would remove some of the history from the piece.

General Advice

As with most collectibles, the beginner is faced with two choices: he can buy only from respected and reputable dealers (who charge a premium for their expertise), or he can invest the time in becoming his own expert. It has been said the true experts know how much they don’t know, and this is particularly true in this country. The real experts are in France, where they have had years of hands-on experience examining original specimens, which are simply not that common over here. The current fashion is to be skeptical of anything that does not adhere to regulation patterns, but the fact remains that non-regulation examples are so abundant that this conservative approach overlooks many authentic pieces. The pressures of wartime production led to many adaptive changes. I recently came across a French grenadier’s cartridge box; research showed it to be a Prussian cartridge box with a French cast grenade on the flap, clearly a captured piece put to good use by its captors. Its unusual appearance was an important part of its history.In the end, the happiest collector is the one who has taken the time to read up on the subject and educate himself in the marketplace. Not only can he avoid being cheated by ignorant or unscrupulous dealers, but he is in a far better position to appreciate the history of the pieces he has in his collection.

Basic Reference Library

The titles below are just a few of those available, and are listed in order of importance. Although most are in French, the pictures are in English! With the exception of Margerand, most are either in print on not that difficult to find.NAPOLEON ET SES SOLDATS (2 volumes), Paul Willing, Collections du Musee de 1’Armee, Paris, 1986.

Crammed with photographs of items in the Museum collection, and as such a very valuable resource.

L’ARMEE FRANCAIS, Lucien Rousselot, p.p., nd.

A series of color uniform plates with detailed scale drawings of insignia and equipment. An absolutely essential reference. The accompanying text is available in both French and English.

AIGLES ET SHAKOS DU PREMIER EMPIRE<, Christian Blondieau, Argout, Paris, n.d.

An excellent book on shako plates and shakos, with many photos.

LA GARDE IMPERIALE, Lucien Fallou, Olmes, Krefeld, 1975

A reprint of the 1901 edition, an important source for the Imperial Guard.

ARMES BLANCHES MILITAIRES FRANCAISES, Christian Aries, n.d

A series of folios with superb drawings of swords — the best reference for edged weapons.

LES COIFFURES DE L’ARMEE FRANCAIS, Margerand, Leroy, Paris, 1905.

Long out of print, but the best single reference on French military headgear

EQUIPEMENTS MILITAIRES, Michel Petard, p.p., n.d.

Excellent drawings of belts, cartridge boxes, belt plates, etc.

The British OSPREY series of books, currently in print, has excellent color plates of uniforms, and often good photos of original pieces.